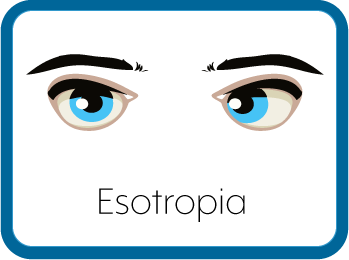

Esotropia

What is Esotropia?

Esotropia is a strabismus condition where the eye turns inward (toward the nose). This condition may be evident intermittently (not all the time) or constantly. The deviation, or eye turn, may occur while fixating (looking at) distance objects, near objects, or both. Esotropia is also often called cross-eyed.

Types of Esotropia

Infantile Esotropia

Much more common than infantile exotropia, infantile esotropia is evident shortly after birth and often before 6 months of age. Infants don't have great eye movement control in the first few weeks of life, but by 6 months the child should have full control of eye movements. Infantile tropia (exo- or esotropia) can be very debilitating to the development of normal binocular vision, as the child starts life unable to develop normal visual skills, such as stereopsis (depth perception). Infantile esotropia is categorized as beginning at birth or during the first year of life.

Acquired

If esotropia develops later in life, it is known as acquired esotropia. It may result from medical conditions, such as diabetes, or other eye problems, such as untreated farsightedness. Double vision is one of the leading complaints of those with the condition. It can make everyday tasks difficult. People with acquired esotropia can often successfully treat the condition with glasses and vision therapy, although surgery may be necessary for some.

Intermittent Esotropia

Intermittent esotropia is a subset of esotropia that is present only once and a while. The patient often can control eye positioning most of the day, but an eye may turn inward with a stressful condition or extended near work.

Accommodative Esotropia

This is technically a subset of intermittent esotropia. Unlike patients that are near-sighted (myopia), patients with a high far-sighted (hyperopia) correction can focus the eye naturally to make images clearer. Naturally focusing an image (called accommodation) is often paired with a slight inward turn of the eyes. High hyperopia patients over-focus to the point that an eye starts to turn inwards abnormally. This is usually corrected with glasses and sometimes bifocals (yes even on kids!). Accommodative esotropia is one of the most common forms of esotropia

Alternating Esotropia

Alternating esotropia refers to how a patient fixates. A patient with a constant esotropia fixates with one eye, all the time. This would be called a unilateral (right or left) esotropia. Patients with an alternating fixation pattern switch fixation between each eye.

Mechanical Esotropia

Mechanical esotropia is often due to fibrosis (or scar tissue) that prevents the eye from moving inward. Some conditions, such as overactive thyroid, can leave deposits in muscles and cause an abnormal tightness for an eye muscle to move. Damage from broken bones around the eye (the area called the orbit) may also limit eye movement.

Sensory Deprivation Esotropia

This often occurs in patients younger than 5 years of age that have severely lost vision in one eye. The brain is unable to fuse the images from the normal eye and the eye that has lost vision, so the eye drifts inwards.

Microesotropia

Microtropias are small deviations of the eye that can be quite tricky to see. Inward microtropia (microesotropia) is much more common than microexotropia.

Signs and Symptoms of Esotropia

The distinguishing sign of esotropia is one or either eye wandering inward. Symptoms may be mild or severe. If suppression of the deviating eye occurs, the patient can have diminished binocular vision and diminished stereopsis. Patients may also experience diplopia (double-vision). Asthenopia (eye fatigue) can also occur with reading.

A cover test may be performed on a distant fixation target, perhaps taking the child to an office window to fixate on an interesting object.

Infants and young children may experience many symptoms such as, loss of 3-D vision, issues with depth perception, and amblyopia (loss of vision in the crossed eye). However, if congenital esotropia is treated in infancy, such complications are less likely to be experienced long-term.

Older children and adults that acquire esotropia can develop some or all of these symptoms, diplopia (double vision), decreased binocular vision (the ability of the eyes to work together), depth perception issues.

Causes of Esotropia

Causes of esotropia are mostly unknown. Children with a family history of the disorder are more likely to get them. They are also common in children who have other systemic (chromosomal or neurologic) disorders.

- No known cause (idiopathic); possibly familial

- Down syndrome

- Cerebral palsy

- Hydrocephalus (Increased intra-cranial pressure)

- Brain tumors

- Trauma

Both esotropia and exotropia may be congenital (present at birth) or acquired (developed later, during childhood).

Other factors to consider that help determine the cause and treatment of strabismus:

Did the problem come on suddenly or over time? Was it present in the first 6 months of life, or did it occur later on? Does it always affect the same eye, or does it switch between eyes? Is the degree of turning small, moderate, or large? Is it always present, or only part of the time? Is there a family history of strabismus?

Neurological Causes of Esotropia

New-onset esotropia is called an acquired esotropia. If the condition occurs rapidly, it's termed acute, acquired esotropia. Most often acute esotropia cases are more concerning because the underlying cause is often damage to the 6th cranial nerve. There is only one cranial nerve the controls the lateral rectus muscle on the ear-side of each eye. This nerve (called the abducens nerve) has a long patch from its origin to the muscle, and can be easily damaged. Head trauma, increased intracranial pressure, diabetes and other vascular disorders, migraines and multiple other conditions could cause a new esotropia.

Treatment for Esotropia

Management of esotropia is based on a number of factors. The overriding principles are:

- Maximization of binocular vision

- Relief of diplopia

- Treatment of associated amblyopia *Re-establishment of ocular alignment

Treatment includes:

- Glasses

- Vision Therapy (also likely in conjunction with glasses)

- Patching

- Surgery on the eye muscles to realign the eyes

For some patients, more than one treatment is necessary to achieve ultimate binocularity. For other patients, some binocularity is achieved and most symptoms diminish. It is important to get treatment if the eye turn is affecting the patients life in an impactful way. Most patients find relief in seeing a Developmental Optometrist for Vision Therapy who specializes in helping the brain use the visual input from both eyes, together. This has a lasting effect for the patient and can often lead to higher self-esteem and reduced overall symptoms of esotropia strabismus.

Esotropia References

The Vision Wiki

- Lazy Eye

- History of Lazy Eye

- Convergence Disorders

- Convergence Insufficiency

- Exophoria

- Esophoria

- Medical Terms

- Accommodation Disorders

- Accommodative Esotropia

- Accommodative Insufficiency

- Amblyopia

- Lazy Eye in Adults

- Strabismic Amblyopia

- Refractive Amblyopia

- Anisometropia

- Critical Period

- Strabismus

- Anomalous Retinal Correspondence

- Transient Strabismus

- Exotropia

- Esotropia

- Hypotropia

- Hypertropia

- Eye Problems

- Binocular Vision

- Physiology of Vision

- Lazy Eye Treatments

- Reading

- Fields of Study

- Research

- Glaucoma

- Virtual Reality

- Organizations